There are different types of long haul patients, but it’s not what you think. Right now, any medical differences between patients are being overshadowed by miscommunication between patients, doctors, and researchers. As I have conducted multiple patient-led surveys, I know that miscommunication happens.

That miscommunication is the worst when the survey is poorly designed. It comes down to:

- People having different ideas about what words mean, e.g. “brain fog” could refer to memory problems. It could refer to difficulty concentrating. Or it could refer to something else entirely.

- People have different styles when answering survey questions. Some people will try to put an answer for every single survey question- even when the survey designer does not want that to happen.

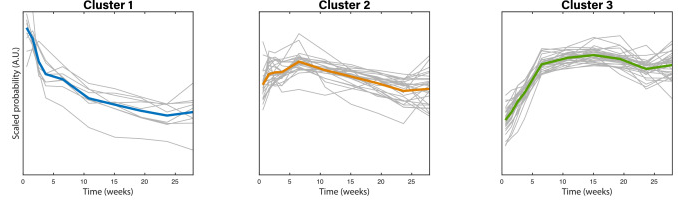

Hierarchical clustering and other techniques can be used to spot different types of patients. In my experience, these techniques find instances where patients are simply answering the survey differently than other people. The ‘types’ of patients depend heavily on how the survey is designed; different survey designs will reveal different styles of answering surveys.

While people talk about a “CFS” or “neuro” form of Long COVID, the data doesn’t support that at the moment. We need better surveys to detect any subtle medical differences that may exist. We also need to recognize that miscommunication is a problem.

What this means for medicine

Firstly, clinicians and researchers should avoid the phrase ‘brain fog’ in almost all situations. It just opens the door to miscommunication and therefore misdiagnosis.

Secondly, nobody is talking about the elephant in the room: miscommunication and unreliable information. While patients hate being not believed, some of them do provide unreliable information. That’s just what happens in the real world. The same applies for researchers and clinicians.

Most of the information out there is unreliable. We need to recognize that so that we aren’t misled into mistakenly thinking that a treatment is safe or effective.

In practice, this likely will not happen among most clinicians. In the mainstream system, there is a strong incentive to follow the herd even if it is bad medicine. This happened for years after it was discovered that antibiotics can treat stomach ulcers and that drugs (and expensive surgeries) aren’t needed to treat them.

Opposition to their radical thesis came from doctors with vested interests in treating ulcers and other stomach disorders as well as from drug companies that had come up with Tagamet, which blocked production of gastric acid and was becoming the first drug with $1 billion annual sales.

Ulcer surgery was lucrative for surgeons who removed large portions of the stomach from patients with life-threatening bleeding and chronic symptoms. Psychiatrists and psychologists treated ulcer patients for stress.

Source: New York Times:

The alternative medicine space and medical freedom movement are no better. Most of these people need to make a living so the only ones who survive are the ones who pretend to know what they’re doing. Accurately reporting what happens to their patients would be a problem for them.

Takeaways for patients

Our healthcare systems (and research institutions) aren’t designed to put patients first. If they were, these issues would have been solved a long time ago and clinicians would have education on how to minimize miscommunication and how to deal with it. They would do a much better job at tracking patient outcomes.

Appendix: Survey data with clustering analysis

Body Politic - https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(21)00299-6/fulltext

Their third cluster (in Fig 6) lines up with how the survey questions are designed.

Source: Questionnaire to Characterize Long COVID: 200+ symptoms over 7 months

Patient Experiences Survey - Patient Experiences Survey – Sick and Abandoned

search for the word cluster